3D printing isn’t just for supercars, now it’s for drone wings, too

Jonathan Gitlin

3D printing or additive manufacturing, as it’s commonly known, serves more to create rapid prototypes in the automotive industry than actual parts for actual cars. Well, mostly. Divergent 3D has been working in the 3D-printed part space for a while, and they have already supplied parts such as subframes to several car manufacturers, including Aston Martin & Mercedes-AMG.

Czinger is a startup that was born from Divergent. It uses Divergent’s technology to build the fastest production car in the world. Kevin Czinger, the company’s founder, was at this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed where we learned that Divergent had diversified its customer base, and now is getting into aviation. They are 3D printing wings to be used by drone maker General Atomics.

Jonathan Gitlin

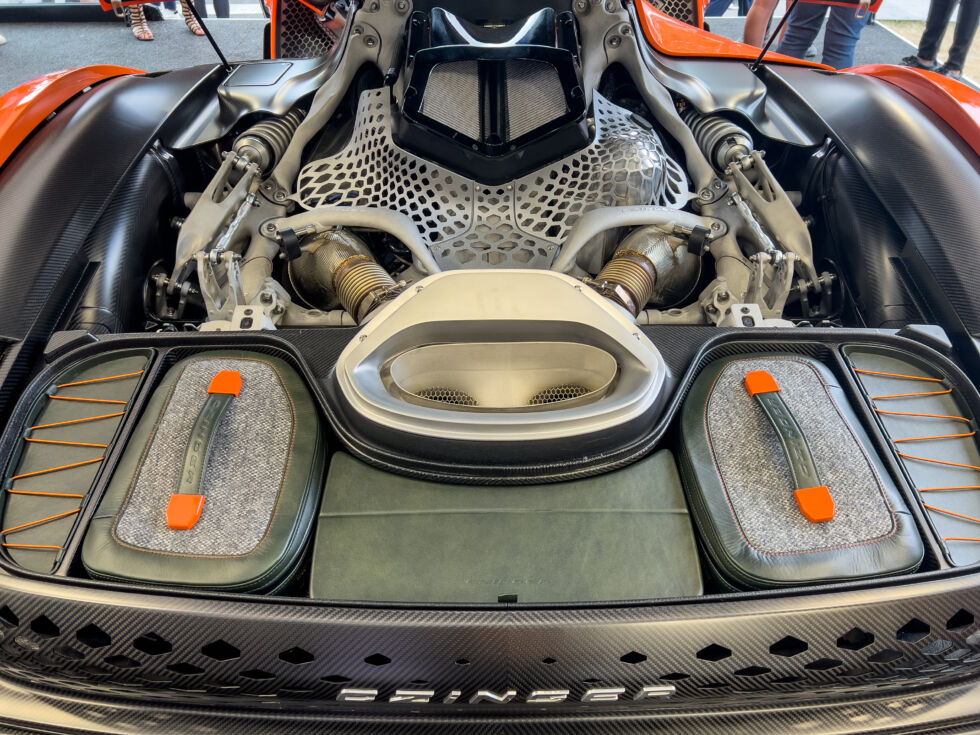

We took a look at the Czinger 21C at last year’s Monterey Car Week—to quickly recap, it’s a tandem-seating hybrid supercar with 1,250 hp (932 kW) and a vast amount of aerodynamic downforce that has allowed it to break production car track records at Laguna Seca and the Circuit of the Americas.

Czinger made the obvious decision to start a car firm in order for Divergent’s technology to be demonstrated. Czinger told Ars that “you don’t really know what tools are going to be until you create an actual product which requires performance and cost-productivity, as well as the material requirements they have.”

“Because, for example, to really print—not to do what people are doing today in terms of prototyping, but to do what we’re doing for the first time on the planet, which is industrial-rate manufacturing—you have to design a printer that is tuned to your material qualities, which in turn are tuned to your specification and requirements of functionality for the product, all of that needs to be designed together,” Czinger explained.

Jonathan Gitlin

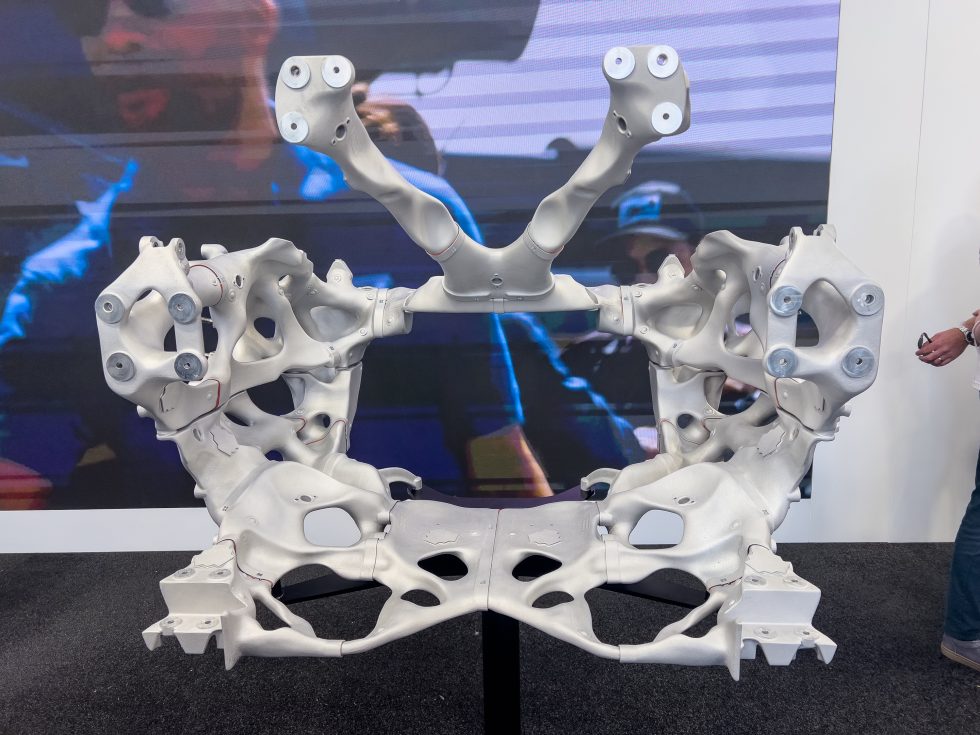

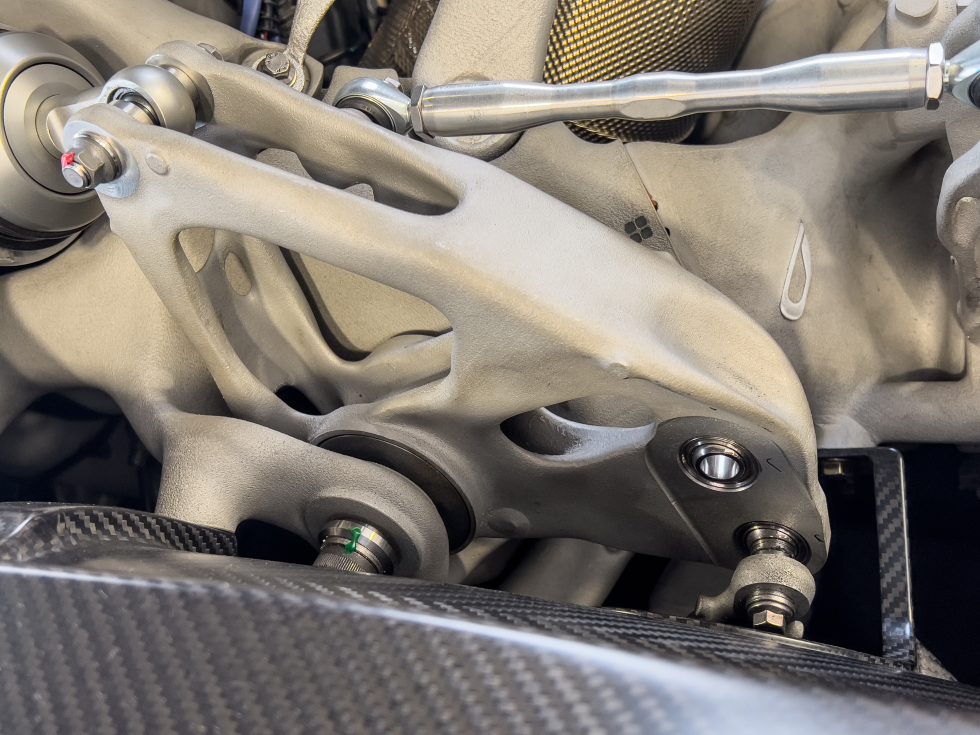

The 21C benefits greatly from the use of 3D printing—parts consolidation has resulted in significant weight savings compared to more conventional construction techniques. The resulting parts appear more organic than any mechanical part you would find in a car. As an example, the brake assembly combines both a caliper, and a suspension, but it has 40 percent less weight than a normal assembly.

“When you go back to the first principles of what is really happening, it’s very similar to evolution.” Nature is a system of energy, right? If you have a competition for energy and material, which is really what it is, then the form will follow function. Czinger stated that when you look at your garden and see how the flora or fauna looks, it’s due to the centuries-long competition of material and energy.

“This is using, really, the big technology innovation of the last 75 years, which is computing power—using computing power to mirror that process of optimization of requirements, performance, to minimize the use of material and energy. He explained that it looks organic because the process is mirrored.

Jonathan Gitlin

Czinger plans to deliver its first 21Cs by the end of this year. “It’s going be a fully crash-certified car, with no exemptions to North American certification.” Czinger said that the vehicle will be emission-compliant in California by 2028.

Not just for car enthusiasts

It was interesting to hear that Divergent expanded its customer base by printing parts for the Aerospace industry. Divergent announced a partnership with General Atomics in February. General Atomics manufactures uncrewed and remote-piloted airplanes.

“They came to see us about a month ago, and told us that they had spent three years developing these smaller drones. It has a 2-meter long fuselage. We’re using laid-up carbon fibre because we want to achieve mass, but it’s taking us 12 days to build and lay up one of these.

He told me that “within three months, using our system, on the first structure we built, provided them with flight ready hardware which reduced the number parts by integrating things like fuel tanks in the skin. We reduced the number parts from more than 180 to 4 and we reduced mass by 5 percent, even though we used our aluminum alloy instead of carbon fiber.”

General Atomics now has more than 240 printed parts flying on test aircraft but says it’s aiming for between 30–80 percent of the parts on a small drone to be 3D printed.